Fleeing from the scene of a car accident may land your DNA in a local police database in addition to a felony charge. Or it may not. Or it may. The regulation of DNA collection practices varies widely between each state and is the subject of back-and-forth legal decisions, as evidenced by People v. Buza in California.

Written by: Greg Emmerich, Promega

The humble beginnings of DNA in the courtroom served primarily as confirmatory evidence linking a suspect to the scene of the crime after they were charged based on other evidence. Now detectives are increasingly turning to DNA databases as the first step in their investigations. California alone had 774 matches to the state’s database from cases in May of 2016, or about 25 matches per day. You may have nothing to hide, yet it has become our civic duty to understand how we should use DNA evidence both effectively and ethically in criminal investigations. Is it useful to drop charges for a nonviolent misdemeanor in exchange for a voluntary cheek swab, as being performed in Orange County, CA, or does that take DNA collection practices too far? Should people convicted of misdemeanors be required to give DNA samples? Here we present the current laws in each state and encourage your thoughts below.

How should we use DNA evidence both effectively and ethically in criminal investigations? Share on X

A brief history of DNA collection laws

In 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Maryland v. King that it is constitutional for police officers to collect DNA samples for any person arrested on a felony charge (but not yet convicted), given that the officer had probable cause for the arrest. There are numerous important details about this decision. For one, DNA evidence is expunged automatically if there is no conviction. The practice specifically covers violent crimes and burglaries, and it does not allow for familial screening. This decision has laid the groundwork for People v. Buza and other future cases; however many states have DNA collection practices that go beyond felony arrests.

DNA collection practices by state

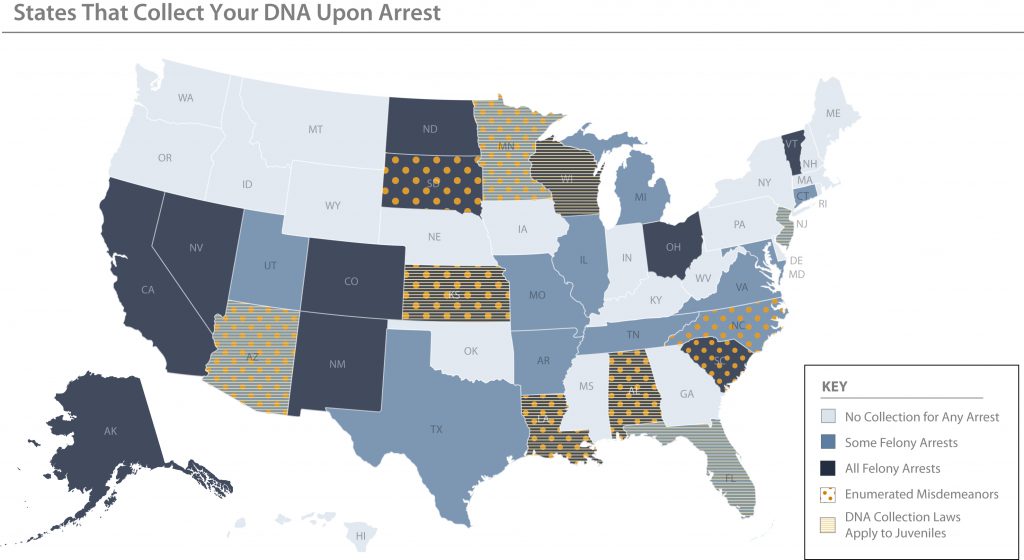

All states have DNA collection practices in place upon conviction; however there are slight variations based on whether or not collection occurs for some misdemeanors and felonies. The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) has the details in this map. What generally receives the most attention from critics is DNA collection upon arrest. Currently 30 states have laws for various crime levels, as you can see below.

Note: Oklahoma only collects DNA upon arrest for individuals unlawfully present under federal immigration law. Source: NCSL with a more thorough state-by-state breakdown here.

The Maryland v. King case establishes that probable cause is needed for DNA collection upon arrest for violent crimes; however only 13 states require probable cause before sample collection or analysis. When an individual is found not guilty, their DNA data can be expunged from police databases. This is an automatic process for 13 states, while 16 states require an individual to submit a request for expungement.

Future implications of DNA testing

Increased demand for DNA collection is not going away, and this demand will only increase the already significant backlog of tests that forensic crime labs already face. These labs are under considerable pressure: from the public that wants to see backlogs eliminated and cases closed, to defendant attorneys who question lab accuracy at every turn, to the state legislature that questions expenditures. Since each state will need to figure out how to budget for an increased demand of DNA testing, it doesn’t seem like a national consensus on when and how DNA samples should be acquired will be achieved any time soon.

Forensic scientists have many issues to confront. The International Symposium on Human Identification brings the leaders in this field together every year and is happening this September in Minneapolis, MN. I will be attending, and I look forward to hearing from people up to their elbows in casework, so feel free to say hi! Conversations like this one about challenges with DNA testing are important for many reasons; scientists also must have the foresight to minimize unintended consequences from their efforts—be they the ozone-depleting nature of refrigerator coolants like CFCs or the means to access our most private information through our genetic code.

[

Greg Emmerich is a science writer at Promega striving to combine creativity with science. He lives off adrenaline rushes from skiing and discovering new music. He received his B.S. Microbiology and M.S. Biotechnology degrees from UW Madison.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!