I have been involved in skeletal remains work for many years. I am fascinated with bones and their ability to survive for such long periods of time in harsh conditions, and I have long been a history buff (so I eagerly accept the challenge of the “few-and-far-between” historical cases when they come along). There is so much publicity tied to current/modern cases (understandably due to the emotional trauma and impact on victims and their families). However, it’s important to note that a primary goal of forensics is to answer questions and solve cases. Sometimes historical cases get overlooked because they fall into the category of being “non-probative” — i.e., all individuals involved may have long been deceased and are therefore not available to participate in court proceedings. However, as practitioners and fellow human beings we should ask the question — does the mere passage of time negate the value of a person’s life or lessen the impact of solving a mystery? In my opinion, these are the coldest of cold cases and still deserve our attention.

Written by: Angie Ambers, Institute of Applied Genetics, UNTHSC

This was a DNA case involving the exhumed skeletal remains of Ezekiel “Zeke” Harper, a famous Confederate guerrilla scout from the American Civil War. Zeke survived the war, but was murdered in a home invasion in 1892. Specifically, this case involved a paternity issue similar to the Thomas Jefferson case (i.e., there was supposition that Zeke had fathered a child with his Native American maid). Below is an introduction to the life of Mr. Harper (who was a very interesting and adventurous character!), as well as a synopsis of the goals of the DNA testing requested.

Born on November 28, 1823, Ezekiel “Zeke” Harper grew up on the family farm along Clover Run in Tucker County, West Virginia. Zeke spent much of his youth exploring the high Alleghenies, part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range that spans the eastern United States and Canada. At the onset of the Mexican-American War in 1846, Zeke volunteered to fight but by 1848 the war was coming to an end and he was never called for service. In the fall of that same year, he left West Virginia and began a journey on foot towards the California gold fields. Along the way he joined a wagon train of “forty-niners” to cross the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevadas. At the time, a series of conflicts known as the Indian Wars were occurring in these regions between Native Americans, American settlers, and the military. Zeke’s skills as a mountaineer and hunter served him well as he trekked across the mountains, but he stopped at several mining camps along the way to work for food. By the time the Indian War in that region ended in late 1849, Zeke was revered by all miners/traders in the area as a lead war scout and mountain guide. In the spring of 1850, he finally arrived at the mines in California and worked there until December 1851. Over the next several years, he continued to prosper as a property owner, cattle baron, miner, and merchant in both California and Oregon.

In 1860, on the eve of the American Civil War, Zeke returned home to West Virginia and immediately sided with the Confederacy. In contrast to the large numbers of soldiers needed to fight in the valleys or flatlands, the steep forested terrain of the Allegheny highlands favored small bands of men who could strike stealthily and then quickly disappear into the brush. Zeke knew the obscure mountain paths and trails and was prized by military leaders as a potential guide and scout. Zeke and his older brother William “Devil Bill” Harper became two of the most famed Confederate guerrilla scouts in the region during the Civil War. In early 1862, Zeke’s scouting efforts allowed him to alert Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson that an army of Union soldiers led by John C. Fremont was advancing through the mountains towards the Shenandoah Valley. His most notable accomplishment as a guerrilla scout occurred during April-May 1863 when he led two brigadier generals in the famous Jones-Imboden Raid, a Confederate attack which destroyed a Baltimore-and-Ohio (B&O) Railroad bridge that was vital to the Union supply lines through western Virginia.

In October 1863, while visiting his parents at the family homestead, Zeke was captured by Yankee soldiers and local Unionists. Over the next several months, he was imprisoned and transported between several Confederate POW camps, including Atheneum Prison in Virginia and Camp Chase in Ohio. In January 1864 he was sent to Illinois’ notorious Rock Island Prison, where he remained until he was traded back to Confederate authorities on February 15, 1864.

Zeke survived the Civil War and returned to Tucker County, where he remained for the rest of his life. Over the years, he accumulated approximately 4500 acres of land and became a renowned country doctor. Sometime between 1878 and 1888, he was rumored to have fathered a son with his Native American maid. In March 1892, Zeke was beaten to death during a robbery and his alleged son was sent to the County Farm, a local orphanage. Sarah Bonnifield Maxwell, Zeke’s girlfriend prior to the Civil War, tracked the child down at the orphanage and took him home to raise as her own.

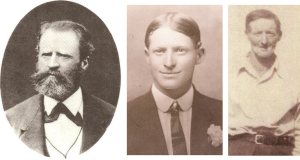

From left: Captain Ezekiel “Zeke” Harper (1823-1892), Confederate guerilla scout during the American Civil War, Earl J. Maxwell (alleged son of Captain Ezekiel Harper) in 1913, Earl J. Maxwell, ca. 1940−1945.

(Photos courtesy of Maxwell family)

This alleged son, Earl J. Maxwell, had seven children who grew up listening to stories about their grandfather Ezekiel Harper. After Earl’s death, his children and grandchildren began pursuing an investigation that could establish their familial link to Ezekiel and substantiate Earl’s claim to be his son. In January 2011, the 21st Circuit Court of Tucker County, West Virginia granted an order for the disinterment of Ezekiel Harper from the Adam Harper Cemetery (Clover District, St. George, West Virginia) for the purpose of DNA testing. Ezekiel’s grave was marked clearly with a well-maintained headstone, as were all of the other graves in the family cemetery.

In collaboration with the Lohr and Barb Funeral Home (Parsons, West Virginia), the exhumation of Mr. Harper’s remains was conducted by the Mercyhurst Archaeological Institute (Erie, Pennsylvania), and select samples were sent to the Institute of Applied Genetics in Fort Worth, Texas for analysis.

Upon exhumation, it was discovered that Ezekiel had been buried in a wooden casket with an apparent inner glass vault/casing, both of which had deteriorated and collapsed under the weight of the soil. Bones with adequate structural integrity were retrieved from the burial site and the following were sent to our lab for analysis: left tibia, right tibia, right femur, mandible, and four teeth (2 canines, 1 lateral incisor, 1 premolar). Bone samples were extracted separately in small batches in a low-copy number (LCN) area of the laboratory. Given the age and condition of the remains, three different extraction methods were used to maximize the probability of DNA recovery. Considering the genetic recombination that occurs in autosomal DNA over the generations within a family, Y-STR analysis was determined to be the most appropriate and informative approach for determining potential kinship (although autosomal DNA analysis was performed as well to assess the efficacy of the different extraction methods used).

Skeletal remains contain limited quantities of DNA that can be substantially degraded. Share on X

Skeletal remains often contain limited quantities of DNA that can be substantially degraded and copurify with environmental inhibitors. Given the age and condition of Ezekiel’s remains, the same contamination controls recommended for archaeological and ancient DNA specimens were used throughout this study. Furthermore, the skeletal remains were stored separately from other samples in the LCN area of the laboratory. A chain-of-custody was maintained, and only one person handled and worked on the bones for the entirety of the project. To prevent cross-contamination from modern sources, the bones were processed and typed prior to collecting reference samples for comparison; hence, the reference samples could not be the source of the profile obtained from the skeletal remains. Additionally, reference samples were processed in a designated high-copy area of the laboratory (separate from the bones, which were extracted and analyzed in the LCN area). All individuals involved in the exhumation and all laboratory personnel were excluded as possible sources of both the autosomal and Y-STR profiles that were obtained from Ezekiel’s remains.

The majority of the DNA isolates from over fifty separate bone sections yielded partial autosomal STR genotypes and partial Y-STR haplotypes. After comparing the partial results for concordance, consensus profiles were generated for comparison to reference samples from alleged family members.

The principal goal of this project was to determine whether a familial link exists between Ezekiel Harper and his alleged son, Earl J. Maxwell. Since Earl J. Maxwell has not been exhumed, no direct samples were available for DNA testing. During his lifetime, Earl fathered seven children, only one of whom was still living at the time of this study. Samples from Earl’s wife and his mother also were not available for testing, and considering the genetic recombination that occurs in autosomal DNA over the generations within a family, Y-STR analysis was determined to be the most appropriate and informative approach for determining potential kinship. Of Earl’s seven children, only two of them were male; the sons of these two males (i.e. Earl’s grandsons) submitted buccal cell reference samples for comparison to Ezekiel’s Y-STR haplotype.

The Y-STR haplotypes obtained from both of Earl J. Maxwell’s grandsons were identical to each other and to the alleles in Ezekiel Harper’s consensus profile at all 17 loci examined. Two separate Y-STR haplotype reference databases were accessed for statistical analysis: the U.S. Y-STR Database (www.usystrdatabase.org) and YHRD (www.yhrd.org). The Y-STR haplotype obtained from the skeletal remains of Ezekiel Harper and from the two alleged grandsons’ reference samples was not found in either database. Since Ezekiel Harper was known to be of European (German) descent, likelihood ratios (LRs) were calculated using sample sizes from similar affine populations. Using Caucasian haplotypes from the U.S. Y-STR database, it is 1667 times more likely to observe the Y-STR results if Ezekiel Harper and Earl Maxwell are paternally related as opposed to being unrelated. With YHRD data for Western and Eastern European Y-STR haplotypes, the LRs are 2500 and 1111, respectively. Using the entire European metapopulation (combined Western and Eastern European), the LR is 3333.

Results of the genetic analyses are consistent with the hypothesis that Earl J. Maxwell is the son of Ezekiel Harper.

This case was published in Forensic Science International: Genetics 9 (2014) 33-41. Aside from my co-authors (which included our lab’s forensic anthropologist, Harrell Gill-King, and Dennis Dirkmaat, the Pennsylvania anthropologist who performed the exhumation), we also collaborated with members of the alleged living descendants of Ezekiel Harper. Dr. George Rhoades and the Maxwell family provided photographs and historical information about Ezekiel Harper and Earl Maxwell (as well as reference samples for comparison). Additionally, Steve French, Civil War historian and author, greatly assisted in gathering biographical records about Ezekiel Harper from library archives and historical letters/diaries. The Lohr and Barb Funeral Home in West Virginia (where Ezekiel was buried) provided copies of the exhumation photographs and historical reference information about burials and casket construction in the late 19th century.

If our methods can work on historical remains, this has enormous applicability to modern cases. Share on X

Although the remains of Ezekiel Harper were more than a century old at this time of testing, consensus profiles of both autosomal STRs and Y-STRs were able to be generated. This type of work on historical and archaeological human skeletal remains involved exploring and testing how well current methods perform with severely degraded, very old bone samples. In our lab, we also are continuously trying to develop new methods that could be more successful on such samples. If our methods can be shown to work on historical and archaeological remains, this has enormous applicability to more contemporary/modern cases where one would expect the DNA to be less compromised. It also may prove useful for remains recovered from mass disasters, mass graves, military conflicts, and in missing persons cases.

What’s Next for You?

I am currently working on another interesting historical case involving several sets of skeletal remains associated with the last expedition of the French explorer La Salle. In 1684, French King Louis XIV sent La Salle across the ocean with four ships to find the mouth of the Mississippi River, establish a colony and trade routes, and locate Spanish silver mines. That plan was never realized. Instead, La Salle lost ships to pirates and disaster, sailed past his destination, and was murdered by his own men. In 1686, La Belle, the one remaining expedition ship, wrecked in a storm and sank to the muddy bottom of Matagorda Bay off the coast of Texas, where it rested undisturbed for over 300 years. In 1996, archaeologists located the 17th century ship and began a decades-long process of excavating the ship and recovering its contents. I recently received a grant from the Texas Historical Commission to perform DNA analyses on human skeletal remains recovered from the shipwreck and Fort St. Louis, the French colony established by the shipwreck survivors (who were shortly thereafter massacred by local Indians). Based on diaries, historical records, and collaborations with French historians, archaeologists and anthropologists from the Texas Historical Commission have ideas about the identities of the deceased individuals; the goal of the DNA testing is to provide positive identification and link the skeletal remains to living descendants.

Dr. Angie Ambers received her Ph.D. in molecular biology from the University of North Texas (UNT) with an emphasis in forensic genetics and human identification. Her dissertation involved an investigation of methods (e.g., whole genome amplification, DNA repair) for improving autosomal and Y-STR typing of degraded and low copy DNA from human skeletal remains and environmentally-damaged biological materials. Dr. Ambers also has master’s degrees in forensic genetics from the University of North Texas Health Science Center and in criminology from the University of Texas at Arlington. Her thesis research involved developing and optimizing a DNA-based multiplex screening tool for the separation of fragmented and commingled skeletal remains. Since 2005, Dr. Ambers has been an adjunct professor at the University of North Texas (teaching molecular biology, genetics, heredity, and human anatomy and physiology). In 2008, she developed the curriculum for a course in forensic molecular biology, in which she teaches DNA analysis/methodology to undergraduate students enrolled in the FEPAC-accredited forensic science certificate program. Before pursuing her doctorate, Dr. Ambers was lead DNA analyst and lab manager of UNT’s DNA Sequencing Core Facility. Her latest work has involved DNA testing of various historical human skeletal remains, including those of an American Civil War guerrilla scout, several Finnish World War II soldiers, unidentified late-19th century skeletal remains discovered in Deadwood, South Dakota, and unidentified skeletal remains from the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Dr. Ambers also recently collaborated with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Forensic Technology Center of Excellence (FTCoE) to develop and disseminate a formal report on the use of familial DNA searching in casework. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the IAG, specializing in characterization and identification of historical and archaeological human skeletal remains.

Dr. Angie Ambers received her Ph.D. in molecular biology from the University of North Texas (UNT) with an emphasis in forensic genetics and human identification. Her dissertation involved an investigation of methods (e.g., whole genome amplification, DNA repair) for improving autosomal and Y-STR typing of degraded and low copy DNA from human skeletal remains and environmentally-damaged biological materials. Dr. Ambers also has master’s degrees in forensic genetics from the University of North Texas Health Science Center and in criminology from the University of Texas at Arlington. Her thesis research involved developing and optimizing a DNA-based multiplex screening tool for the separation of fragmented and commingled skeletal remains. Since 2005, Dr. Ambers has been an adjunct professor at the University of North Texas (teaching molecular biology, genetics, heredity, and human anatomy and physiology). In 2008, she developed the curriculum for a course in forensic molecular biology, in which she teaches DNA analysis/methodology to undergraduate students enrolled in the FEPAC-accredited forensic science certificate program. Before pursuing her doctorate, Dr. Ambers was lead DNA analyst and lab manager of UNT’s DNA Sequencing Core Facility. Her latest work has involved DNA testing of various historical human skeletal remains, including those of an American Civil War guerrilla scout, several Finnish World War II soldiers, unidentified late-19th century skeletal remains discovered in Deadwood, South Dakota, and unidentified skeletal remains from the 1974 Turkish invasion of Cyprus. Dr. Ambers also recently collaborated with the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) and the Forensic Technology Center of Excellence (FTCoE) to develop and disseminate a formal report on the use of familial DNA searching in casework. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the IAG, specializing in characterization and identification of historical and archaeological human skeletal remains.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!