Today’s blog is written by guest blogger Edward Humes. Reposted from The ISHI Report with permission.

She was in her twenties, homeless, out of money, living in an old car with two young sons, their father in the wind. She was pregnant again. Nine months pregnant. But she didn’t show much, and layered against the winter chill in baggy clothes, she knew no one could tell. This lonely secret was both blessing and curse, she knew. It was all too much.

I can’t keep this one, the woman had been arguing with herself. There’s no money for diapers, or formula, or pretty clothes, or any clothes. I want better than that for this child.

When the time came, she dropped her boys off with a friend and made an excuse for why she’d be gone overnight. The next day, the Saturday before Thanksgiving, she parked in an empty lot and gave birth at five in the morning, cold and alone. She stared down at her new daughter. They cried in tandem.

When the dark sky lightened to gray, she drove the streets of Anaheim, California, looking for signs of life. She found them at an Alpha Beta supermarket on a busy street ten minutes from the city’s great secular mecca, Disneyland. She saw workers bustling around the market, getting ready to open for the new day. This was her chance.

When no one was looking, she placed her two‑hour‑old baby, wrapped in a faded yellow blanket, by a milk crate next to the store’s grimy trash bins. Then she got back in the car and drove off. Someone would find her, the mother figured. Soon.

Sure enough, within minutes the market’s janitor followed the sound of soft crying to the trash bins. He stared down at a dark‑haired baby on a milk crate, the infant smeared with blood and amniotic fluid, a portion of umbilical cord still attached and draped over the tiny belly. The temperature hovered in the low fifties that morning and the skimpy blanket could not protect the baby’s hands, feet, and face. Her fingers and toes were cold to the touch and tinged blue. The janitor shouted for help and other store workers raced over. One tried to warm the small hands in her own, while a coworker ran back inside to call the police. The first officer on the scene put the baby in his squad car and cranked up the heat as high as it would go until the paramedics arrived and whisked the infant to the hospital.

With the excitement ended and the workday resumed, no one at the Alpha Beta noticed an hour later when a woman with an expression both anguished and furtive drove by the store, staring at the trash bins. The mother had returned to make sure her baby had been found. Satisfied, she drove off and never told anyone, not friend nor family, about the child she had left. The father never even knew she had been pregnant.

At the hospital, the neonatologists checked on the baby’s condition. Other than a mild case of hypothermia, she was perfectly healthy. The all‑too‑practiced official response to child abandonment lurched into motion then: the police launched a search for the parents while the county’s social services agency sought a temporary foster home. The next day, the local Orange County Register Sunday paper dubbed the child “Baby Alpha Beta.”

The baby had come into the world on November 21, 1987, the same day eighteen-year-old Tanya Van Cuylenborg most likely left it, raped, murdered and left half-naked beside a lonely country road in northern Washington State. And, three decades later, that little girl in her thin yellow blanket would also be the key to figuring out the identity of Tanya and her boyfriend Jay Cook’s killer.

Fostered and eventually adopted by a nurse entranced by the tale of the infant abandoned at her local supermarket, Baby Alpha Beta became Kayla Tovo. Kayla thrived in her adoptive home, though learning the story of her origins was hard. Eventually the hurt and anger gave way to her belief that there was a reason she hadn’t been put inside the dumpster but next to it instead. She hadn’t been thrown away. She had been left to be found, left for a better life, left to be saved.

After growing up, serving in Afghanistan, weathering grievous wounds from a bomb blast, then returning home to start her own family, Kayla felt the need to search for her roots. In 2014, she connected through social media with CeCe Moore, who had left acting to become a pioneer in the new field of genetic genealogy. Moore and a small band of other citizen scientists were turning the quaint old hobby of family‑tree building into a secret-busting powerhouse, leveraging the reach and rapid growth of consumer genetic databases to do something new: use DNA to find people who weren’t actually in any consumer or criminal justice DNA database.

Moore had Kayla spit into a tube and send it to the consumer DNA company 23andMe. The results, combined with Moore’s combing of archival records and social media posts, allowed her to reverse engineer Kayla’s family tree, finally putting her in touch with her birth mother in October 2014. And her brother. And other biological relatives. The saga had come full circle, from the front‑page headlines about the discovery of Baby Alpha Beta just before Thanksgiving 1987 to the family reunion 27 years later, once again on the same front page.

CeCe Moore had accomplished a first: she solved a crime solely through genetic genealogy with techniques of her own devising. Not that she discussed it in terms of a criminal investigation. To her, it was a search for a foundling’s identity, a quest to reunite child and birth mother. But child abandonment is a crime. And that’s how it would have been treated at the outset had Baby Alpha Beta languished too long alone in the cold. Then it would have been a murder investigation—one that remained an unsolved cold case until Moore came along.

The full import of her accomplishment and methods with Baby Alpha Beta wouldn’t be clear to anyone for the next few years—not even Moore herself—until her path crossed with a cold case detective by the name of James Scharf. Then she would put those same methods to the test not to reunite a family, but to hunt down a killer who had destroyed one.

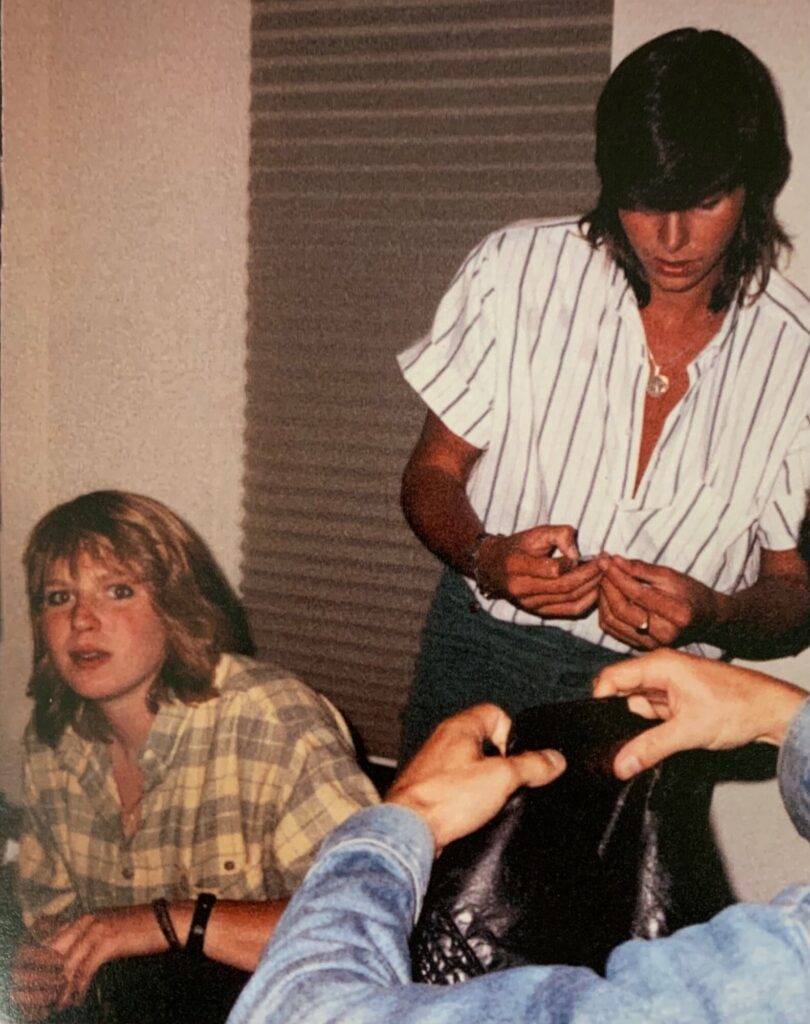

The case that would become the world’s first genetic genealogy murder trial began on November 18, 1987, with a trip to Seattle from one of Canada’s most lovely and temperate spots, Vancouver Island. Tanya Van Cuylenborg and Jay Cook, on their first road trip together after five months of dating, took on an errand for Jay’s dad, volunteering to fetch a new furnace for the family heating service and repair business. The journey by van and ferry should have taken about five hours, with a planned return the next evening. But the couple never reached the furnace supplier. Investigators later traced their movements to Bremerton, Washington, where they purchased a ferry ticket to Seattle, the last leg of their trip. There the trail ended. They had vanished.

Over the next week, family members searched along their route—until Tanya and Jay’s bodies, their van, and a cache of their personal possessions were found one after another in different locations across 60 miles and three Washington counties. Massive media coverage, an international manhunt, even an episode of Unsolved Mysteries came and went. No eyewitnesses or murder weapons were found. There were no cell towers or traffic cams back then to track. And crime-scene DNA, preserved in 1987 and uploaded into every iteration of CODIS since 1994, drew blanks.

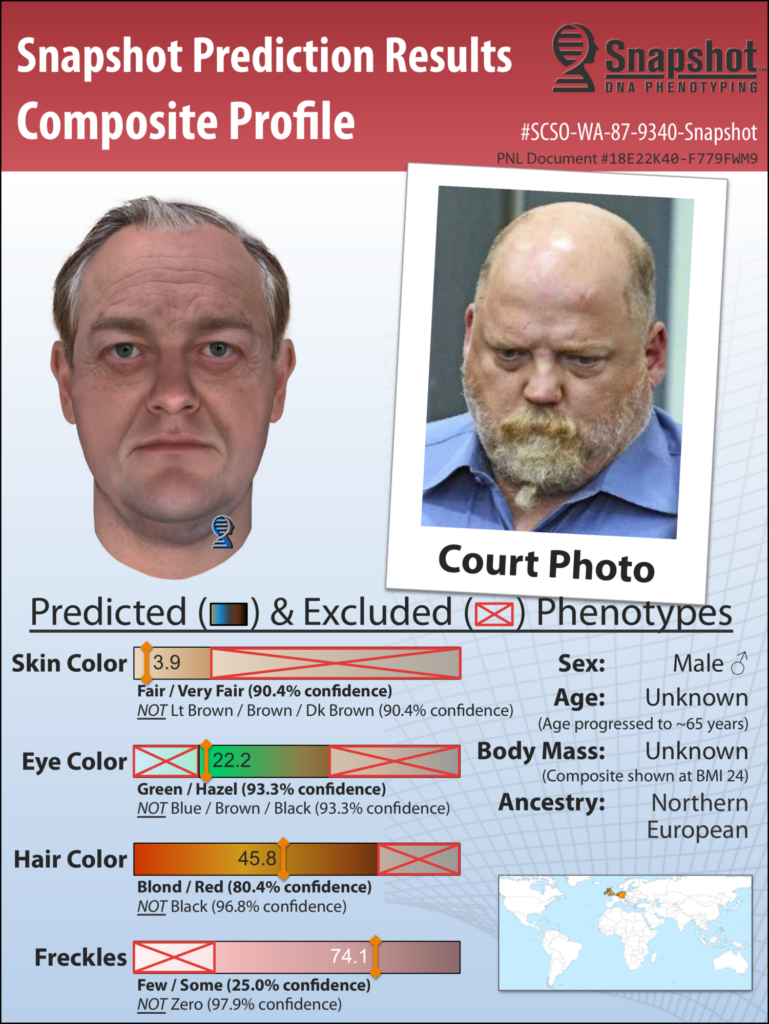

Thirty years passed. Scharf, a cold case detective for the Snohomish County Sheriff, had spent years doggedly combing through old files and developing new leads in the case. He had lost count of the suspects he had sought out, checked out, and ultimately ruled out because their DNA didn’t match traces left behind by Tanya and Jay’s killer. In 2017, he turned to Parabon Nanolabs’ “Snapshot” phenotyping, a technology based on information-rich SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) DNA profiles, which the company originally developed for the military. The resulting physical description and composite image drew a flood of new tips from the public, most of them fruitless. What Scharf didn’t know at the time was that, by then, the Reston, Virginia, company was trying to expand its law-enforcement services by bringing in CeCe Moore.

Moore had longed to take on cold case crimes with genetic genealogy for years, despite being rebuffed by skeptical forensics experts at ISHI conferences and elsewhere. But she faced another more discouraging barrier: The terms of service for the crowd-sourced consumer DNA database she relied on, GEDmatch, didn’t authorize uploading profiles of crime suspects at that time. She had evangelized GEDmatch as a tool for uniting families, Moore said. There was no way she would use their DNA for a purpose they never envisioned or even knew existed—implicating those same family members in crimes. Instead, she suggested Parabon start building acceptance of genetic genealogy crime solving through something the site did welcome: identifying John and Jane Doe crime victims. But before that effort could get off the ground, everything changed.

Others had done what Moore had refused to do, using GEDmatch (and two other databases) to identify a notorious serial rapist, murderer and burglar, best known as the Golden State Killer.

The April 2018 arrest in that case, and the novel manner in which Joseph James DeAngelo Jr. was identified as the culprit, sparked global headlines—and consternation among some genetic genealogist insiders over privacy and consent. GEDmatch’s owners responded within days with a bannered notice on the site informing users that it had become a crime-solving tool without their knowledge or permission. At the time, GEDmatch was a small hobbyist project run on the honor system and based out of a retiree’s Florida bungalow. The owners could not police the police or detect violations of the terms of service. So, they suggested anyone who did not want their DNA used in this way should delete their profiles from the site.

As Moore and Parabon saw it, this announcement lifted the ethical barrier holding their cold case aspirations back. The genie was out of the bottle, and everyone knew it. This would eventually create a rift in the tight-knit community of genetic genealogy adepts, with some arguing that notice was not the same as consent. But Parabon had 100 crime-scene profiles in hand from phenotyping and ready to go, with police agencies clamoring to put them to work solving cold cases.

The first case they decided to tackle: Finding the killer of Tanya and Jay.

And, once again, everything changed.

When the Golden State Killer story broke, it was depicted as a moonshot‑level effort, with months of time and manpower behind a complex genealogical hunt. The conventional wisdom was that there’d be no rush to solve other cases that way, because the resources simply didn’t exist to do more than a handful. And this seemed to make sense. But only if you didn’t know just how much one CeCe Moore on her couch with an open laptop could accomplish.

That story flipped in a hurry when Jim Scharf led a press conference a few weeks later on the arrest of a suspect in Tanya and Jay’s murder. A stunned press learned this startling fact: a genetic genealogist got involved for the first time with the case just a couple of days after the Golden State Killer’s arrest, then solved a thirty‑one‑year‑old mystery in two hours.

The revolutionary nature of this accomplishment soon became clear: this had not been a one-off, it was the wave of the future, neither too complicated nor too hard nor too slow to replicate. Genetic genealogy wasn’t the backstory anymore. It was the story.

“It if hadn’t been for genetic genealogy,” Jim Scharf told them, “We wouldn’t be standing here today.”

Dozens of more solved cases followed, then hundreds, the vast majority the work of Moore and Parabon. A new age of forensic DNA investigation had arrived, not from the crime labs or the Justice Department or research universities, but from our collective fascination with our roots, the ingenuity of a few citizen scientists, and a baby girl left behind a dumpster near Disneyland.

Postscript: A Seattle trucker, William Earl Talbott II, with no criminal convictions and no DNA profiles on file anywhere, was identified by Moore, confirmed by DNA fingerprinting conducted by the Washington State Patrol Crime Laboratory Division, convicted by a Snohomish County jury, and sentenced to life without possibility of parole in 2019. Last year, a state appeals court granted Talbott a new trial because of alleged jury bias revealed during voir dire. The Washington Supreme Court is reviewing that decision. At oral arguments recently, several justices wondered aloud why this appeal should prevail, given that the defense had not used its numerous remaining challenges to remove the juror, but had instead accepted the jury panel on the record at the time of trial…

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!