Today’s guest blog is written by Cairenn Binder, Director of Education and Development at DNA Doe Project; Director, Investigative Genetic Genealogy Certificate Program at Ramapo College of New Jersey; Founding Partner of Coast to Coast Genetic Genealogy Services.

Investigative genetic genealogy (IGG) has become a leading method for restoring the names of the long-term unidentified since its inception in 2017/2018. As an investigative genetic genealogist and Director of Education and Development at the nonprofit organization DNA Doe Project, I am among the lucky few privileged to take part in this important humanitarian effort.

Last year at ISHI 2021, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to share the story of a Jane Doe whose identification using investigative genetic genealogy was complicated by two consecutive generations of misattributed parentage. In the poster and blog Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: How Misattributed Parentage and Other Challenges Can Complicate Your Investigative Genetic Genealogy Case, my work as an investigative genetic genealogist was made tangible and accessible through the case study of this young woman and the arduous journey to find her identity.

When considering my submission for ISHI 2022, I had a strong desire to share case studies that further highlight the humanitarian aspect of decedent identification. DNA Doe Project is approaching its 100th identification, and through dozens of cases our mission remains focused on the restoration of each person’s identity and reunification with their loved ones.

Often, our work is assisted by the clues that the unidentified left behind. For my submission to ISHI 2022, I opted to share stories of cases I led wherein the decedent’s own mementos either helped or hindered efforts to identify them with IGG.

Clues such as jewelry and tattoos can provide leads in human identification where there is otherwise little to go on. While these artifacts are usually not as helpful or reliable as advents in DNA testing, they can provide supporting evidence when a candidate is discovered using investigative genetic genealogy.

…

The first case I shared in my poster this year was that of “Annie Doe”, now known to be Anne Lehman.

In 1971, the remains of a murdered young girl were found in the woods near an Oregon highway. The only clue to her identity was a ring with “A.L.” scratched by hand into the mother of pearl surface. She was called “Annie Doe” for her red hair, and for nearly 50 years she remained unidentified. It was a surprise to all involved when her nickname turned out to be shockingly prognostic – “Annie’s” true name, Anne Lehman, was uncovered by the DNA Doe Project in 2019.

The DNA Doe Project team working on her case had identified a genetic downline of interest from her English ancestors; a family who had moved to the pacific northwest. A daughter of theirs, Anne Lehman, was of greater interest to the team in large part because her initials matched the ring found with “Annie Doe”‘s remains, in addition to the genetic matches providing evidence of her identity. In this particular case, genetic matches in GEDmatch were limited due to recent immigration on both her maternal and paternal family lines. As a result, circumstantial evidence including geographic information and her ring were important factors in increasing the team’s confidence in submitting Anne to our partner law enforcement agency as a candidate.

Anne Lehman’s identity was later confirmed with a family reference sample provided by her sister.

…

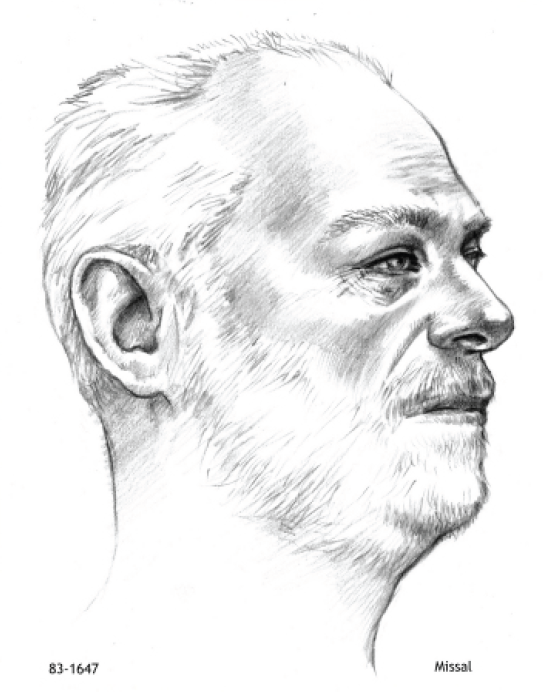

In 1983, Baseline John Doe was found deceased in a field in Phoenix, Arizona. He was a victim of homicide and his killer was later identified, but was unable to provide any information regarding the man’s identity. DNA Doe Project began working on his case in 2021 and identified a candidate just weeks after genetic genealogy research began.

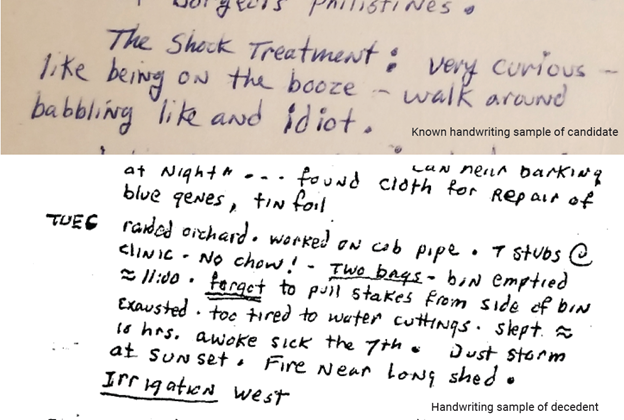

Unfortunately, the candidate had no direct living relatives for whom an STR profile could confirm identity. As a result, the medical examiner’s office in this case relied on other sources of information. In addition to comparison of SNPs between the candidate and his living niece, as well as family tree information and a proof of life search, a comparison of handwriting was conducted.

The candidate’s niece provided a known writing sample from the candidate, which was compared to journals and event logs in the decedent’s personal belongings found with his remains. Notably, neither the handwritten journals or the known writing sample contained a lowercase “N”; this comparison lent further credence to the already robust compilation of research, allowing the medical examiner’s office to identify the decedent.

…

Items found with a decedent can also be “red herrings” that do not support their identification. One such example is the brassiere found with Karen Kaye Knippers.

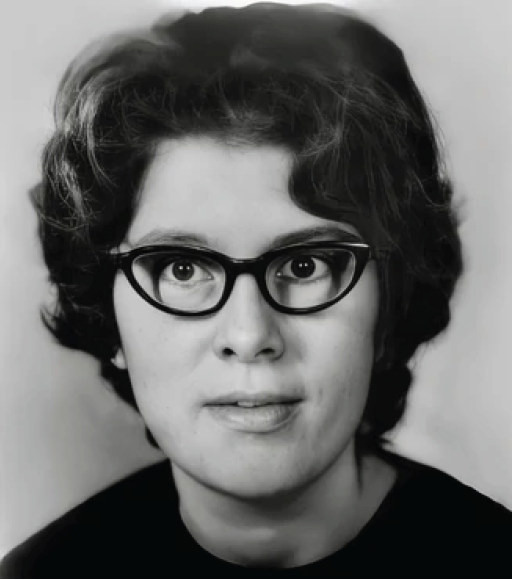

The remains of a female homicide victim were discovered in 1981 in Pulaski County, Missouri. The only clue to her potential identification was a name written on her brassiere, “Jubel” or “Julie”. The investigators working to identify her later utilized isotope analysis to determine she had likely grown up in the southeast United States.

In 2019, the Pulaski County Sheriff’s Office (PCSO) consulted DNA Doe Project to aid in the identification of Pulaski Dixon Jane Doe. While working the family trees of genetic matches, her team searched for the names “Jubel” and “Julie”, but ultimately the candidate Karen Kaye Knippers was identified as a likely candidate for the identity of Pulaski Dixon Jane Doe. This lead was provided to PCSO in December 2019.

In May of 2021, Karen Kaye Knippers was confirmed to be Pulaski Dixon Jane Doe, through confirmation by a family reference sample obtained from her sibling.

The “Jubel” brassiere turned out to be a red herring, providing no clues to her identity. Thankfully, the family trees of her genetic matches in the investigative genetic genealogy process resulted in the clues necessary to provide a lead to her identity.

…

While analysis of genetic matches is the most important aspect of investigative genetic genealogy, artifacts and personal effects of the deceased can be combined with other identifying evidence to increase confidence of the IGG practitioner providing an investigative lead to a law enforcement partner.

Sharing of information between the IGG practitioner and investigating agency is paramount to the success of identification, as evidenced by cases in which mementos and artifacts provided additional clues leading to the identification of the John or Jane Doe.

I was pleased with the reception of this poster presentation at ISHI 2022 – during the poster sessions, I was afforded the opportunity to network with professionals of diverse backgrounds in the field of human identification. The desire of those in our field to hear more about the people impacted by our work through the sharing of case studies was tangible.

I look forward to sharing more stories at ISHI 2023 and beyond. In the coming year, I will continue to lead educational programs at DNA Doe Project and will teach my first IGG courses at the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Center at Ramapo College of New Jersey. Additionally, I continue to perform investigative genetic genealogy work through both DNA Doe Project and Ramapo College, in addition to the LLC I co-founded, Coast to Coast Genetic Genealogy Services.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!