Today’s blog is written by guest blogger Jordan Nutting, Promega. Reposted from The ISHI Report with permission.

On October 19, 2020, in a corner of what was once the African American section of the Potter’s Field in Tulsa’s Oaklawn Cemetery, a backhoe begins scraping away layer after layer of red Oklahoma earth. Workers in high-visibility vests and orange hard hats prepare to join the excavation. DeNeen Brown, a reporter with the Washington Post, looks on, bearing witness to a site that could be one of the final, unmarked resting places for victims of a massacre that happened 100 years in the past.

The Tulsa Race Massacre is “one of the worst single incidents of racist terror violence committed against Black Americans in U.S. history,” said Brown, who has been covering this search and the ongoing impacts of this massacre since 2018. Finding the victims’ graves would “help provide some healing and some closure” in a century-old story.

On day two of the excavation, the team of archaeologists, geologists and forensic anthropologists unearth a single grave with human remains. On day three, they find the outlines of at least ten more coffins. On day four, the last day of the excavation, one more coffin emerges. Because of the fragile state of the remains, the team covers the unearthed coffins in protective materials and reburies them for a later, detailed exhumation.

Nine months later, in June 2021, the team reopens the site. In addition to the 12 remains unearthed in October, they discover 23 more graves. Only one of the graves has a marker. No markers or other records for the people buried in the other 34 graves exist. Of the remains, 19 bodies are in a good enough state to exhume.

As anthropologists and archaeologists methodically catalog the site and examine the bodies, they also collect bone and teeth samples for DNA analysis, the first steps in what could be a multi-year process to identify the people buried in these unmarked graves and their living descendants—and figuring out if these people are victims of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.

What Happened in Tulsa?

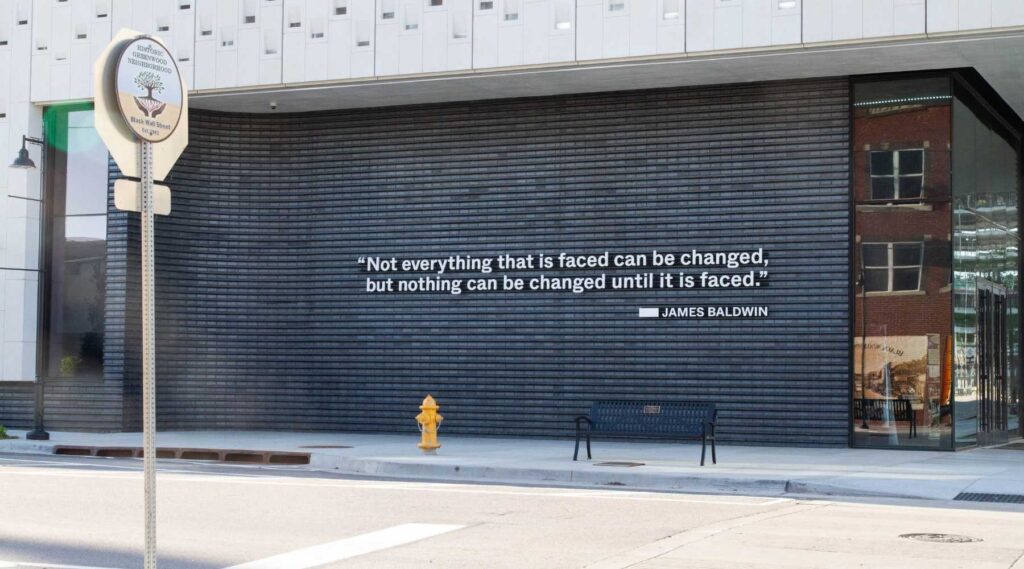

In the early morning hours of June 1, 1921, an armed mob of white men entered Tulsa’s predominantly Black Greenwood neighborhood, where, over the next 16 hours, the mob’s campaign of arson and violence left 35 city blocks destroyed, over 10,000 Greenwood residents homeless and, historians estimate, about 300 people dead (1). Previously, Greenwood had been a center of notable prosperity: Booker T. Washington referred to it as “Black Wall Street”. There were movie theaters, two hotels, a bank and many other Black-owned businesses and homes. But photographs taken after the attack show these same businesses, churches and homes reduced to rubble and ashes.

These events took place only two years after what is now called the Red Summer of 1919. During this period, dozens of racially motivated attacks against Black people were committed across the U.S., including Washington D.C. and Chicago. Historians estimate that 800 Black people were killed throughout the state of Arkansas during this summer (1).

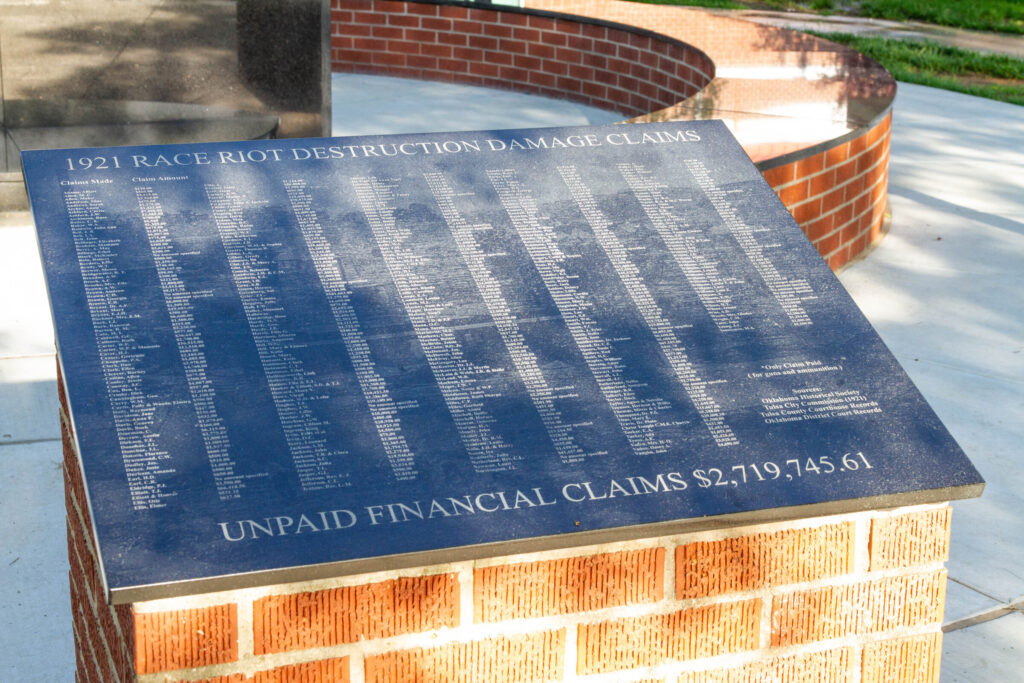

Despite being one of the most violent racial attacks committed in U.S. history, the events of June 1, 1921 went largely unacknowledged for nearly 100 years. No arrests or punishments were brought against those who were involved in the massacre. In fact, a Tulsa city commission report made in the two weeks after the attack laid the entire blame on Greenwood’s Black residents (1). Brown’s own father, who grew up in Tulsa, never learned about the attack in school lessons about state or city history.

The first official report of the events surrounding the attack wasn’t published until 2001, eighty years later (2). In 1996, the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 was formed, and over the course of five years the Commission gathered and analyzed oral histories and thousands of historic documents. Forensic anthropologist Clyde Snow, known for his work in identifying mass graves in South America, assisted in the investigations.

One of the Commission’s key findings was that certain actions during the massacre were sanctioned by state institutions. During the attack, Tulsa’s police chief deputized hundreds of white residents, giving them the right to arrest and detain Black residents. Local newspapers also influenced events. On May 31, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune published an inflammatory article on the front page that called white residents to “nab” a young Black man who allegedly attacked a female elevator operator while she was working in a Greenwood bank (3). The subsequent arrest of this Black man—Dick Rowland—is cited as the spark that set off the massacre.

Where Are the Bodies?

At the time the 1996 Commission was studying the massacre, only 39 victims had been confirmed. Historians, however, believe that close to 300 people were killed in the massacre.

“Many of the survivors of the massacre and the descendants of survivors believe it is essential that these bodies be found, and they be given a proper burial,” said Brown. “Where are their bodies? Where are they?”

In a 1999 search for these missing bodies, a team from the University of Oklahoma used ground-penetrating radar to do preliminary scans of an area of Oaklawn Cemetery that historians thought could be a massacre burial site (2). The team did identify anomalies that suggested unmarked graves were present. However, the site wasn’t excavated until 20 years later after the newly elected Tulsa mayor, G.T. Bynum, called for an investigation (1).

Experts from the University of Oklahoma and the Oklahoma Archaeological Survey, and Dr. Phoebe Stubblefield, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Florida who contributed to the 1996 Commission’s report, led the excavation of this site (4). Their excavation, which was carried out in in collaboration with a Public Oversight Committee, yielded only various pieces of old debris—the team didn’t find any graves. But radar scans indicated that a different area of Oaklawn Cemetery also had anomalies consistent with burial sites. The team’s October 2020 excavation of the site unearthed at least 12 graves.

When the site was excavated again in July 2021, the team carried out a full archaeological, geological and forensic analysis. A report from the investigation team details their findings (4). Notably, underneath one coffin, the team found fragments of a glass bottle with a manufacturing date embossed on the base—1921. The bodies were also examined for any evidence of trauma, something that would help bolster evidence that some or all these people were killed in the massacre. Two bullets were recovered from one of the bodies, a man with African ancestry.

After the gravesite investigation concluded, the bodies were reburied in gray steel coffins during a June 30, 2021 ceremony.

DNA Genomics Enters the Story

Though the location, timing and condition of the bodies found in the Oaklawn Cemetery site are consistent with the bodies belonging to victims of the 1921 massacre, more evidence is needed to confirm their identity and their place in history. To that end, the City of Tulsa commissioned Intermountain Forensics, a non-profit genomic forensics lab, to carry out DNA analysis of the remains in hopes of developing genetic genealogy profiles.

Intermountain Forensics was selected after more than six months of conversations with the city of Tulsa, the Oversight Committee and community stakeholders said Danny Hellwig, CEO of Intermountain Forensics. “This is a very sensitive project and there’s a lot of moving parts, so we spent quite a while just talking things through. It turned out to be a real match made in heaven.”

Intermountain Forensics uses in-house expertise and lab capabilities along with outside partners to carry out forensic genetic analysis of human remains, rape kits and other samples used within the legal system. “Our mission is to take very difficult samples, very difficult DNA cases and apply technology towards them to get to a good result,” Hellwig said.

The remains from the Oaklawn Cemetery excavation may be their most difficult case yet. Intermountain has previously extracted DNA from saliva on letters dating back to 1880, so they have shown they can gather useable DNA from century-old samples. However, the bodies found in Oaklawn Cemetery were not well preserved.

“You’ve got difficult sample types, bone and teeth, that don’t have a lot of DNA to start with, and these samples were not preserved well,” Hellwig said. “They’re in rough shape, and they’re 100 years old.”

In preparation for working with bone and teeth samples collected from the unmarked graves, Intermountain Forensics has been working to validate various pre-processing methods that can provide maximal yields of any remaining intact DNA in the samples. For example, Intermountain Forensics partnered with Qiagen and Dr. Rachel Houston, a professor in the Forensic Science department at Sam Houston State University, to test new techniques for extracting high yields of DNA from tooth samples. Using control samples, they used Qiagen’s Tissuelyzer II to crush human teeth into a fine powder within a tube coated in DNA stabilizing reagents. Validation data showed that the crushing and extraction method worked as well, and—in some cases—better than other techniques for extracting DNA from bone and teeth. Hellwig is optimistic that this system can be applied to the Oaklawn Cemetery samples.

Intermountain Forensics’ main goal for this project is to eventually create a genetic genealogy profile for each recovered body. With these profiles in hand, the team will be able to start the search for potential matches in genetic genealogy databases. A match could help identify living descendants of the people buried in Oaklawn’s unmarked graves and potentially learn who the bodies belong to.

However, Hellwig says, that task is going to be “a bit of a needle in a haystack.” Even with a genetic profile from the Oaklawn grave remains in hand, making a match is impossible unless profiles from the right family lines are present in databases. And that’s a challenge because “the genetic genealogy databases are woefully underserved by the African American Community and people of color in general, and there’s really good reasons for that, considering how marginalized and victimized some of these communities have been in the past.” A 2020 report from the California Law Review found, for example, that DNA profiles for Black people are disproportionately overrepresented in forensic DNA databases compared to other groups (5).

To bolster the odds of finding matches, Intermountain Forensics is working with the Oversight Committee and community stakeholders to do outreach and to put out calls for people with possible past family connections to Tulsa and Greenwood to submit DNA samples for genetic genealogy profiling.

“We need to establish a lot of trust and we intend to, but make no mistake, this project doesn’t work if we don’t get the community support we need,” said Hellwig.

If Intermountain Forensics manages to generate genetic genealogies for the bodies buried at Oaklawn Cemetery, they will move to carry out other genetic analyses. Methods like Y-STR analysis, mitochondrial DNA analysis and next-generation sequencing can help provide a more detailed genetic profile and improve the ability to establish matches with living descendants.

Learning from the Past

The story of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre is one that laid dormant for nearly 80 years. Even after the 1996 Commission released their findings, which included photographs, court records, recordings of survivor interviews and ground-penetrating radar survey results, it took another 20 years before the City of Tulsa took on the task of locating the bodies of victims (2, 4).

As Hellwig has been telling people about Intermountain Forensics’ work, he’s found that most people know nothing about the Tulsa Race Massacre, and “that is just tragedy beyond tragedy.”

Though learning about what happened in Tulsa on June 1, 1921 is one way to wrestle with that tragedy, Brown notes that it’s only one piece of a story that is still unfolding across the U.S. For example, Brown sees similarities between how the Tulsa Race Massacre went unmentioned in Oklahoma history books for decades and recent efforts to ban books discussing racial violence from schools.

“People have to know history, because if you don’t know it, it’s going to repeat itself,” said Brown.

Now, thanks to the combined efforts of scientists, community organizers, reporters and government officials, there is a chance that the bodies found in Oaklawn’s unmarked graves will again have names, and their place in history will be revealed.

Learn more about forensic sciences and the Tulsa Race Massacre at the 33rd ISHI meeting this fall. DeNeen Brown will be giving the meeting’s keynote presentation, and Danny Hellwig and Dr. Phoebe Stubblefield will also be presenting.

References

- Silvers, J., Dir. (2021) Tulsa: The Fire and the Forgotten. Saybrook Productions, Ltd. https://www.pbs.org/video/episode-1-zew2v8/

- Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 (2001). Tulsa Race Riot. https://www.okhistory.org/research/forms/freport.pdf

- Walker, M. (2021) Tulsa Race Massacre: Newspaper Complicity and Coverage. Headlines & Heroes: Newspapers, Comics & More Fine Print. https://blogs.loc.gov/headlinesandheroes/2021/05/

- Stackelbeck, K.L. and Stubblefield, P. R. (2022) Archaeological and Forensic Research in Support of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Graves Investigation: The 2020–2021 Field Seasons at Oaklawn Cemetery. Oklahoma Archeological Survey Research Series 11. https://www.cityoftulsa.org/media/18139/sensitivecontentarchaeologicalandforensicresearchinsupportofthe1921tulsaracemassacreinvestigation-1.pdf

- Murphy, E. and Tong, J. H. (2020) The Racial Composition of Forensic DNA Databases. California Law Review 108, 1847. https://www.californialawreview.org/print/racial-composition-forensic-dna-databases/#clr-toc-heading-33

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!