Today’s blog is written by guest blogger, Angie Ambers, MA, MS, PhD (Henry C. Lee Institute of Forensic Science) and Mike Ware, JD (Innocence Project of Texas). Reposted from The ISHI Report with permission.

Shortly before midnight on December 10, 2010 (a Friday night), patrons of Club Blur (a bar in the Montrose district of Houston, Texas) watched in horror as a young man was beaten and stabbed to death in the parking lot. None of the witnesses knew the victim or the perpetrator, nor were they privy to the events that led up to the brutal murder. The Houston Police were called and, throughout the night and the next day, eyewitnesses provided video-recorded statements to investigators. Accounts from eyewitnesses varied in some ways, but were consistent in other respects. The victim had run into the parking lot and up the steps leading to the front door of the bar. He begged to be permitted to enter and to be protected from someone who was trying to kill him. The victim was a Caucasian male in his 20s. Bar employees failed to understand the seriousness of the situation and refused to let him inside the club for sanctuary. The perpetrator appeared moments later. He was an African-American male described as being 6’0”-6’6” tall, weighing approximately 200-260 lbs, in his late 20’s or early 30’s, and in athletic condition. He was well-dressed and wearing an orange shirt. The perpetrator and the victim scuffled in the parking lot; at one point during the struggle, the victim broke loose, but was ultimately caught and murdered. The perpetrator walked away into the night.

The following evening — Saturday, December 11, 2010 — Lydell Grant was parking his car in the parking lot shared by Club Blur and adjacent establishments as he prepared to meet friends at a neighboring bar. One of the employees of Club Blur who had witnessed the murder the night before saw him and believed he looked similar to the perpetrator. Indeed, Lydell Grant was an African-American male who otherwise fit within the broad and general descriptions provided by eyewitnesses. The bar employee wrote down the vehicle identification number (VIN) of Mr. Grant’s car, called Crime Stoppers to report the sighting, and eventually collected a cash reward for the information.

Based on the Crime Stoppers tip, Houston Police investigators assembled a photo lineup of six African-American males, including a photo of Mr. Grant. Over the next day and a half, all six eyewitnesses selected Mr. Grant’s photo as that of the perpetrator. The lead detective was allowed to administer the identification process in a non-double blind manner. In other words, he was aware of which photo was the “suspect” as he displayed the spread and observed each eyewitness as they were deciding on a choice. This approach permitted the detective to influence and/or cue the witness during deliberation and to reinforce their decision when they chose the suspect (or, in other words, when they made the “right” choice). Six months later, the Texas legislature would pass a law discouraging such procedures as these procedures have led to hundreds of wrongful convictions of innocent people.

The following week Lydell Grant was arrested on a murder warrant. He professed his innocence and had a solid alibi for the night of the murder. Nevertheless, he was immediately adjudged guilty in the media and through public comments of the Houston Police Department. Two years later, in December 2012, he was convicted of the murder based on the strength of testimony of six eyewitnesses who had identified him in a police photo spread. The jury completely disregarded Mr. Grant’s alibi and he was sentenced to life imprisonment.

During trial, a forensic DNA analyst who worked for the Houston Police Department Crime Laboratory testified that she had tested the victim’s fingernails collected during autopsy in an effort to obtain the DNA profile of the perpetrator (i.e., from skin cells that may have transferred during the struggle in the parking lot). She testified that there was at least one unknown male donor to the DNA mixture (i.e., there was a DNA profile present in the mixture that was not the victim’s profile). She first testified that it was “inconclusive” whether Mr. Grant could be excluded as the “unknown male donor” to the mixture. Upon further prodding by the prosecutor, she testified that this meant that Lydell Grant “could not be excluded” as the unknown male donor to the mixture. This testimony, in conjunction with the eyewitness identification, was obviously damaging to Grant’s case and contributed to the guilty verdict.

Post-conviction, Mr. Grant lost all of his appeals and he eventually contacted the Innocence Project of Texas (IPTX) for help. Mike Ware is the Executive Director of the Innocence Project of Texas, a non-profit committed to identifying and exonerating innocent individuals who have been wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for criminal offenses they had nothing to do with. IPTX receives 50-100 letters per month from incarcerated individuals claiming innocence and requesting assistance with their case. Mr. Ware also teaches an experiential law school class (clinic) at the Texas A&M School of Law in which students assist in identification of cases in which the convicted defendant may have a viable post-conviction claim of actual innocence. The phrase “actual innocence” means either: 1) a person was convicted of a crime that occurred much as the police, witnesses, and prosecutors claim it occurred, but it was committed by a completely different person (e.g., cases of mistaken eye-witness identity); or 2) a person was convicted of a crime that never occurred at all (e.g., the conviction was for arson, but it turns out the fire in question was the result of legitimate electrical problems in the building infrastructure).

In 2018, IPTX and Texas A&M Law School Clinic began reviewing Mr. Grant’s case. There were many proverbial “red flags” indicating a possible wrongful conviction, beginning with the manner in which pre-trial identification procedures (i.e., the police photo lineups) were conducted. Moreover, Mr. Grant had a corroborated narrative of innocence in his alibi. These factors alone supported that the case merited further review, study, and investigation. Fairly quickly, law student Jason Tiplitz noticed something was off with the DNA evidence. Mr. Grant appeared to be clearly excluded from the DNA mixture recovered from the victim’s fingernails. When compared to the actual trial testimony in which the State’s forensic DNA analyst testified that Grant could not be excluded, another red flag was raised. The significance of foreign DNA found under the victim’s fingernails in this kind of case was not lost on the police, even before DNA testing was performed. An early investigative report noted that the victim’s fingernails should be collected and analyzed for DNA, and that any results obtained should be compared to known suspects and searched against the CODIS database.

Post-conviction review of the DNA evidence

In January 2019, Ware contacted Dr. Angie Ambers, a forensic DNA expert and Assistant Director of the Henry C. Lee Institute of Forensic Science in West Haven, Connecticut. Ware requested that Dr. Ambers review the DNA mixture recovered from the victim’s fingernails during autopsy and preliminarily assess if Grant’s DNA was potentially present in the mixture. After studying the DNA mixture for a short period of time (less than 30 minutes), it became obvious that an unknown (foreign) male profile was present – that is, an autosomal STR profile from a male who was not the victim or Lydell Grant.

This finding is unfortunate because the discovery and confirmation of an unknown male contributor in the DNA mixture could have guided the investigation to find the true perpetrator, and likely could have prevented the wrongful conviction of Mr. Grant. Post-conviction review of the DNA evidence also elucidates issues surrounding the quality of defense sometimes provided to defendants. During trial, Mr. Grant’s defense counsel did not hire an independent forensic expert to review the DNA evidence and did not cross-examine the State’s expert on the DNA data interpretation.

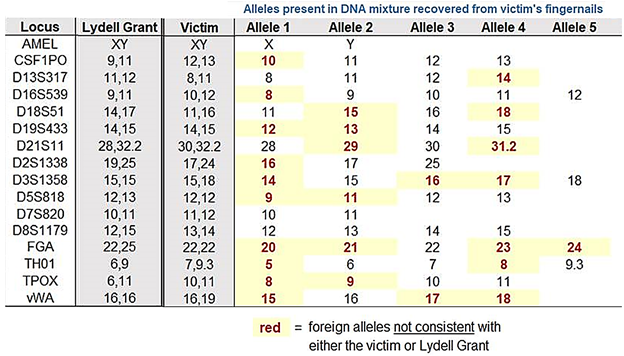

In terms of post-conviction review of the DNA mixture, it should be noted that the original testing conducted in 2011 involved typing of 15 autosomal STR loci (including the 13 core CODIS loci) plus amelogenin, for a total of 16 loci tested. The formal case report issued by the crime laboratory stated that “a mixture of DNA from at least two (2) individuals, at least one of whom is male, was obtained from this item. The victim cannot be excluded as the contributor to the major component of this DNA mixture. No conclusions will be made regarding Lydell Grant as a possible contributor to this mixture.” Although inconclusive statements in DNA laboratory reports are often viewed as a conservative approach to avoid making erroneous inclusions or exclusions (which could lead to wrongful convictions or false acquittals, respectively), this case illustrates the need to further consider the implications of “inconclusive” statements regarding DNA mixtures. In this case, it was not difficult (for a trained eye) to recognize the presence of a foreign male contributor. Given that, as a matter of practice, DNA case reports are shuffled through several internal technical reviews prior to finalization and release, it’s concerning that none of these review steps elicited discussion about the apparent exclusion of Mr. Grant from the mixture.

For simple presentation purposes (and not intended as a formal analysis), Figure 1 displays the DNA mixture data obtained from the murder victim’s fingernails and identifies the foreign alleles present in the mixture that do not belong to the victim or to Lydell Grant. In total, there were twenty-six (26) alleles present in the DNA mixture that are not consistent with the STR profiles of the victim or Mr. Grant.

Based on Dr. Ambers’ initial assessment that there was an obvious foreign male contributor present in the mixture, Ware and IPTX contacted the Harris County District Attorney Office’s Conviction Integrity Unit to request the raw data (.fsa) files from the original DNA testing that was conducted in 2011 for analysis using probabilistic genotyping. Years after Mr. Grant’s conviction, there was widespread adoption of probabilistic genotyping as an improved methodology for DNA mixture deconvolution. Probabilistic genotyping greatly reduces subjectivity in interpretation and is considered superior over the manual CPI/CPE calculations conducted previously by forensic DNA laboratories across the U.S. After receiving the files from the Conviction Integrity Unit, the raw data was submitted to Cybergenetics in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for analysis using TrueAllele®, one of two commonly implemented probabilistic genotyping software programs (along with STRmix™) for forensic DNA mixture interpretation. TrueAllele® analysis of the DNA mixture recovered from the murder victim’s fingernails definitively excluded Mr. Grant as a contributor to the mixture and confirmed the presence of an unknown male profile. Further exploratory processing with TrueAllele® generated an allele list for the unknown contributor that met the criteria for searching in CODIS. In June 2019, with the assistance of a CODIS administrator from the Sherriff’s Office in Beaufort County, South Carolina, a CODIS search was conducted and resulted in a hit.

The CODIS hit was to a man who fit the description of the murderer given by the six eyewitnesses (Figure 2). His name was Jermarico Carter and he lived in Houston, Texas at the time of the murder. He had previously been arrested on a drug-related charge within feet of where the murder took place. More importantly, he had a violent criminal history and, although he had previously spent time in prison, he was not incarcerated at the time of the murder and he left Houston shortly after the crime was committed (relocating to Atlanta, Georgia). It was Jermarico Carter’s DNA recovered from the murder victim’s fingernails.

Six months later, in December 2019, the new suspect Jermarico Carter was arrested in Atlanta, Georgia on other charges. The Houston Police were notified, and detectives from the Cold Case unit flew to Atlanta. During the police interview and interrogation, Carter confessed to the murder but claimed it was “self-defense.” He has now been formally indicted for the murder and is awaiting trial in Harris County.

Lydell Grant’s exoneration

Legal professionals and forensic DNA experts from four different U.S. states (Texas, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, South Carolina) worked on this case, on behalf of Mr. Grant to prove his innocence and to promote justice for the victim and his family. Subsequent to Mr. Carter’s arrest and confession, Lydell Grant’s post-conviction appeal filed by the Innocence Project of Texas was supported by both the Harris County District Attorney’s Office and the District Judge. It has been pending in front of the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (TCCA) for 16 months, still with no decision by the Court. In mid-2020, the TCCA asked that the case be remanded back to District Court, that the District Court and the DA’s office ask the six eyewitnesses at Grant’s trial to formally respond to Grant’s innocence claims, and that the District Court provide the TCCA with a photo of Jermarico Carter, the confessed murderer now in jail, dated circa 2010 (when the murder was committed). In recently released court documents, one of the six eyewitnesses has stated on record that, at the time of the original investigation, he told police that he didn’t see the suspect in the photo lineup. According to the court documents, the eyewitness stated that he was then told to “look again” and eventually chose Grant as a suspect. As of the date of this article, the TCCA still has not made a decision regarding Lydell Grant’s request for exoneration.

WOULD YOU LIKE TO SEE MORE ARTICLES LIKE THIS? SUBSCRIBE TO THE ISHI BLOG BELOW!

SUBSCRIBE NOW!